☙ History ❧

The Great Market of Haarlem in 1740 where Koster is said to have lived and worked in the 15th century (at "No. 2"), and where his image continued to be displayed in the façade of that house for posterity and "for eternity" — although the house suddenly collapsed and was destroyed in 1818.

Þe History & Mystery of

Þe Legend of Koster

Once upon a time, it is said around the year 1370, there was born a man in the city of Haarlem, in the Netherlands, by the name of Laurens Janszoon Koster (var. Coster). In his life, he was purported to have held a variety of modes of employ, from candle-maker and innkeeper, to sheriff, treasurer and an officer of the city guard, but most notably and assuredly he held the position known in Dutch as koster (meaning sacristan, sexton or warden) of the great church of Haarlem, a position which at that time was one held in high esteem, and hence he used that surname, Koster, as was a common practice in that age.

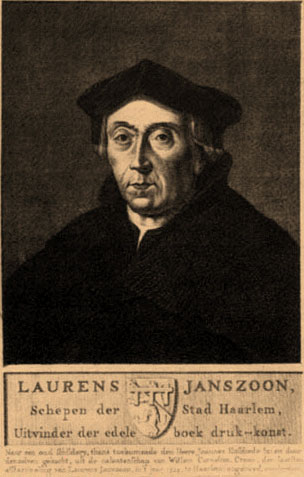

The earliest known portrait of Koster, as shown in Petrus Scriverius’ Laure-crans voor Laurens Coster (1628). Other, similar-looking portraits depicting Koster can be found, however, this is the first one upon which those others are based. Note the letter “A” that he holds in his hand.

As a magnate of that fine city, in or around the year 1423 (by some accounts as late as 1428 or 1430) he found himself walking in the nearby woods one day with his grandchildren, and for their amusement he began to idly cut letters from the bark of a beech tree. The letters fell into the sand, and from the impression that they left the idea came to him that letters such as these might also be impressed upon paper in order to print books — and thus, in that inspired moment, was planted the seed that would later become the invention in Europe circa 1440 of the wondrous art of printing with moveable type, an innovation which came a dozen-odd years before Gutenberg printed his acclaimed 42-line Bible (from 1452 to 1455).

"Homage to Laurens Jans. Koster at the Celebrations of the Fourth Centennial held in Haarlem the 10 and 11th July 1823" Koster sits in the woods, with a knife in his right hand and a finished letter “A” in his left hand. Engraving by D. Sluyter, after a drawing by A.G. van Schoone (1823).

Koster sitting in the woods, looking with awe at the first impression made of a letter “A". Painting by J.A. Kruseman for the fourth centennial celebrations (1823).

Koster sitting in his workshop, stamping out letter by letter the words “haerlem koster mccccxx...". On the table are various letter stamps and a saucer of ink. Ibid.

Scene from the London play The First Printer, with “Koster” and “Gutenberg” on the stage. Here Koster offers printing to the world, proclaiming like a prophet endless blessings as a result of his invention. Woodcut from The Illustrated London News for March 15, 1856.

Hadrianus Junius, who has held the noble reputation of being the most learned man in the Netherlands after Erasmus, was the first to give the full account of the legend of Koster in his Batavia, published posthumously in 1568. In addition to the above story of the initial idea and discovery, he relates how Koster then went on to experiment with block printing and improve the quality of ink employed (as the ink generally used by scribes tended to run when used in a press) and, with the help of his son-in-law, Thomas Pieter, produced the book Speculum Humanæ Salvationis, and then continued to improve his methods with various types of wood, then lead, and finally mixtures of lead and tin.

A page from the Batavia (1568) by Hadrianus Junius, the oldest printed reference naming Koster as the inventor of printing, showing the passage referring to him.

The bindery of Laurens Janszoon Koster. Engraving by Jan van de Velde after a design by Pieter Janszoon Saenredam, in Petrus Scriverius’ Laure-crans voor Laurens Coster van Haerlem, Eerste Vinder vande Boeck-druckery (1628).

The bindery of Laurens Janszoon Koster. Ibid.

The Speculum Humanæ Salvationis, which has long been held to be the oldest book printed in the Netherlands, and the first work of Laurens Janszoon Koster.

Prospering with his invention, he hired a number of assistants, including one Johannes Faust. It was this Faust, as the story goes, who himself became adept at the art of printing and casting type, and who on Christmas Eve of 1441 then broke into his master’s shop, stole all of his types and equipment, and fled to Amsterdam, then on to Cologne and, finally, to Mainz.

An engraving depicting the theft of Koster’s printing materials on that fateful Christmas Eve by his disloyal servant Johannes Faust (from a series by Koster & Zeelander, 1823).

Could this legend be true? There are no books in existence which carry Koster’s name as printer — however, this is not necessarily evidence in favour of Gutenberg as neither are there any which bear his name.

In addition, although Koster is not mentioned specifically until 1568 in Junius’ Batavia, the matter of Haarlem being the birthplace of printing had indeed arisen some years earlier in Jan Van Zuyren’s work on the Invention of Typography, wherein he wrote regarding that city’s claim that these facts were “...at this day fresh in the remembrance of our fathers, to whom, so to express myself, they have been transmitted from hand to hand from their ancestors.” This is further supported by Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert, in his preface to a translation of Cicero printed by him in 1561, where he states similarly in reference to Koster and the city of Haarlem that “...the faithful testimonies of men alike respectable from their age and authority, who not only have often told me of the family of the inventor, and of his name and surname, but have even described to me the rude manner of printing first used, and pointed out to me with their fingers the abode of the first printer."

Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert’s preface to a translation of Cicero, Officia Ciceronis, leerende wat yeghelijck in allen staten behoort te doen (1561), wherein he affirms the claim of Haarlem being the birthplace of printing.

Yet, we stand today with the most widespread consensus and teaching generally being that printing was invented in Mainz, Germany around the year 1452 by Johann Gutenberg — although even modern scholarly texts on the subject do not entirely discount the possibility that, indeed, Gutenberg was not the first. Warren Chappell’s oft-referenced A Short History of the Printed Word, published in 1970, states that the “quality of the early Dutch type-making and printing still extant is so markedly inferior to Gutenberg’s that the possibility of a few years’ priority is less important than Gutenberg’s results.” He goes on to defend this not-wholly neutral position with the justification that the “chief value of establishing earlier experiments lies in their helping to explain the extraordinary quality of the great 42-line Bible [of Gutenberg]” — in other words, it would appear that he feels that Gutenberg should be immortalized with the honour of being the principal inventor of the printing press for the sake of aesthetics more than for any reason related to historical accuracy or fact!

Nevertheless, for hundreds of years the believers and proponents of the story of Koster have stood fast in their conviction that he was, indeed, the inventor of printing prior to Gutenberg, and that apart from the Speculum, he also printed the Biblia Pauperum, the Ars Moriendi and the Donatus, and amongst these believers have been scholars equally as eminent and qualified as those who would support Gutenberg as discoverer of this art.

With holidays, celebrations and grand centenaries held in that great city of Haarlem and throughout the Netherlands for what have now been all these hundreds of years, with endless tributes — books, paintings, sculptures, coins, medals and memorial statues — all in honour of the man, and with Dutch schoolchildren still being taught to this day the proud story of their fellow countryman’s historic achievement, perhaps ultimately the best we can say that we are left with is that we might never truly know which of these two strongest of candidates really was, in fact, the inventor of moveable type in Europe. Whether flimsy myth or genuine fact, however, surely the story of Laurens Janszoon Koster is indeed the stuff of legend, and certainly one well worth the telling.

Even if it is a legend which should prove to be steeped only in eternal mystery...

Engraving by J. Houbraken, after a drawing by Taco Jelgersma, included in the book De stad Haarlem by Van Oosten de Bruyn (1765).

Questions? Comments? Bug report?

☞ Contact Psymon ☜

All text, graphics and web design of this entire site

are copyright © Ron Koster / Psymon, 1998-2021 (except as otherwise noted)

and may not be reproduced or distributed in any manner

without explicit permission of Ron Koster / Psymon.

All Rights Reserved.